HIS STORY

Rise to Samurai

William Adams and his shipmates had arrived in Bungo domain, subject to Catholic missionary activity for nearly 50 years. The Jesuits had a strong presence, knew full well that the existence of Dutch and English Protestants in Japan would be unlikely to work in their favour, and did their best to persuade the local authorities that the unexpected and unseasonal ship was a pirate vessel. Piracy had been rampant in Japanese waters until recently, and the penalty was unambiguous: death.

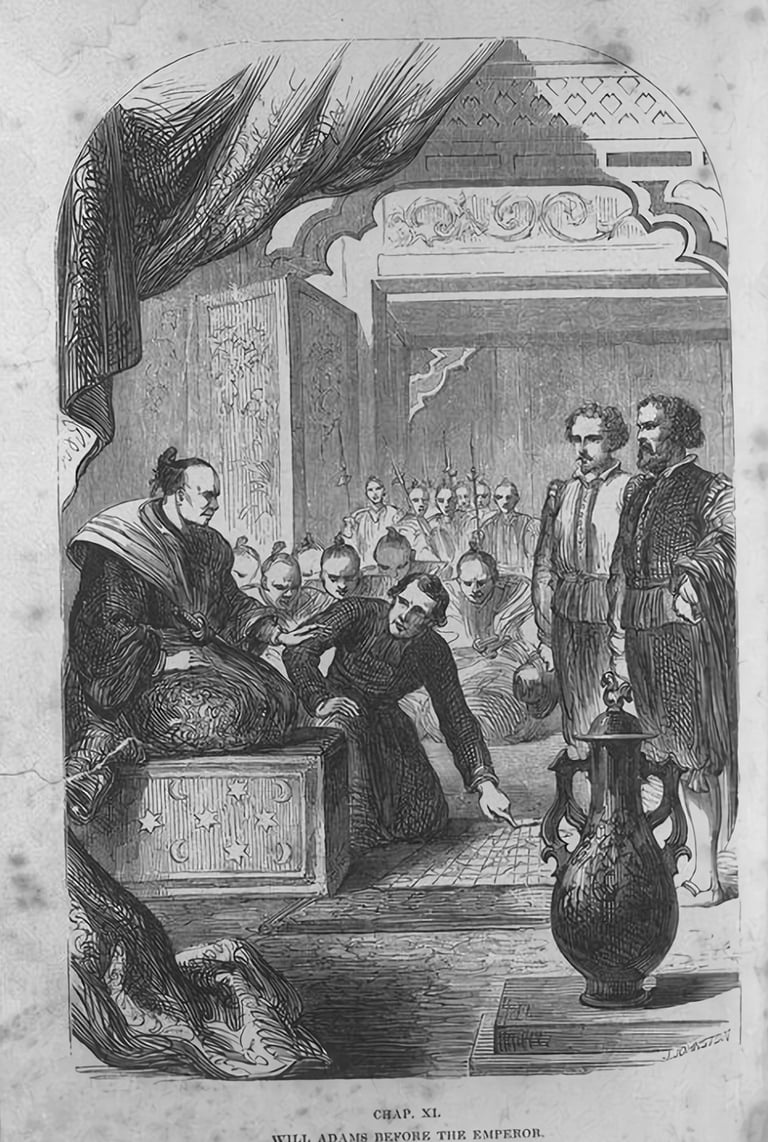

Fortunately for Adams, and the rest of the crew, the authorities followed proper procedures, declined to listen to the Jesuits’ pleas for the death penalty, and reported the incident to the most powerful lord in the land, Tokugawa Ieyasu. He ordered that the Englishman be taken to Osaka, where the great warlord interrogated him personally.

A Dutch 18th century depiction of William Adams meeting with Tokugawa Ieyasu. (Credit: Wikimedia)

Ieyasu, who was soon to be appointed Shogun, seems to have been impressed with his captive, and slowly but surely over the next few years, put him to work in a variety of roles. Adams’ expertise in mathematics, geography, and knowledge of inter-European relations was tapped. Furthermore, Japanese accounts say that the Englishman had a remarkable talent with artillery, and worked with the Tokugawa troops on their gunnery. Ieyasu also ordered Adams, who had become commonly known by his professional title Anjin which means pilot in Japanese, to build ocean-going vessels in the English style as an experiment. Two small ships were constructed at Ito, one of which later crossed the Pacific to Acapulco to repatriate the Governor of the Philippines who had been shipwrecked in what is now Chiba Prefecture, near Tokyo.

These shipbuilding feats seem to have raised Adams to a position of great respect in Ieyasu’s eyes, as his opinion and counsel was frequently sought when matters European raised their head. He was also appointed interpreter and consulted when receiving Spanish and Dutch delegations, displacing the Jesuits who had traditionally acted in these roles.

Adams’ voice at court only became more influential, as insensitive and arrogant Spanish diplomacy rubbed Ieyasu and his vassals the wrong way, dashing any hopes of increased intercourse and trade with New Spain, and the Philippines (as a province of New Spain was also was subject to Mexico City’s rule.)

An 1866 depiction by William Dalton of William Adams first meeting with Tokugawa Ieyasu. (Credit: Wikimedia)

Adams was not present at Ieyasu’s court in Sunpu when the first Dutch mission made its initial appearance under the leadership of Broeck and Puyck. The trade privileges they were granted, however, had been previously arranged by Adams in 1608. By the time Adams reached Hirado in 1609, to meet the Dutch, their delegation to Sunpu had already departed. Future Dutch missions to Sunpu (led by Specx in 1611 and Brouwer in 1612) ensured that Adams would meet them at Sunpu rather than Hirado. It was during these later missions that the prospect of establishing the Dutch factory at Uraga was discussed. On both occasions the Dutch were put off by continued Spanish presence in the harbour.

A key to Adams’ success was his ability with languages. It is believed that he was conversant or even fluent in Spanish, Dutch and Portuguese before arriving in Japan, and he swiftly learned the language, and pragmatics, of his adoptive homeland. That he also found family stability in the early years of his stay was also likely to have been a contributing factor. Sometime, perhaps as early as 1602, he married a lady of adoptive Samurai rank named Magome Oyuki. Adams' new father-in-law was highly influential in trade and business in Nihonbashi, where all roads to the effective capital, Edo (modern-day Tokyo,) terminated. The counsel of an intelligent wife and good family connections undoubtedly assisted his rise in Japan.

In recognition of his services, in 1610 Adams was appointed Hatamoto, a high Samurai rank. With the status came a fief worth the considerable tax-rights of 250 koku and even his own retainers, at Hemi in modern-day Yokosuka. He was now a low-ranking lord, and became part of Japan’s ruling class. The final "reward" for service to his new Tokugawa lord was a prohibition on leaving the country until further notice. Adams had become so valuable that Ieyasu preferred to keep him on hand as a clan vassal, even granting him the extremely rare right of personal audience. This was a great honour, but all the prestige and riches were in fact to compensate for a well adorned, and highly gilded, cage.

Of course, Adams’ English family life was disrupted, never to be revived, although he did manage to send funds to his first wife Mary in later years. He seems to have been resigned to this, and made the most of his new situation. Adams and Oyuki had two children between them, Joseph and Susanna, and it is believed he fathered another child on Hirado Island where he spent a lot of time due to its trade connections. After his death, Joseph inherited his rank and became head of Adams’ Japanese household, being known by his father’s professional appellation "Anjin," with the local area, "Miura," established as the surname.

In 1609, a Dutch East India Company mission arrived to establish relations with Japan. Ieyasu was delighted, because it ended the monopoly on European trade which the Portuguese had enjoyed. He ordered Adams to facilitate their welcome.The Dutch, with Adams as their representative at court, obtained the right to travel and trade freely in the country under the Shogun’s personal protection. Despite Adams and Ieyasu strongly hinting that they should establish their base of operations at Uraga, within easy reach of Edo and its huge potential market, they declined and were permitted to set up a trading post on the island of Hirado, strategically placed in a trusted pro-Tokugawa domain, with excellent maritime access to their South East Asian bases.

In gratitude for these unheard-of privileges, Adams was employed as an agent to help sell Chinese silks and other imports.

Subsequently, in 1613, an English East India Company (EIC) mission under the command of Captain John Saris succeeded in navigating to Japan. One can well imagine Adams’ delight at hearing his mother tongue spoken for the first time in well over a decade.

Through Adams, the English and Japanese rulers exchanged letters and gifts. King James I of England, who was also James VI of Scotland, was given two suits of fine Japanese armour, and Ieyasu received the first telescope to ever leave Europe. The EIC was granted equal trading rights to the Dutch, with special provisions made regarding possible exploration of a long-theorized ‘Northern Passage’ between Japan and Europe through the icebound wastes which were known to exist far beyond Japan’s most northern reaches.

The long relationship between the two countries was off to a good start.

Adams was employed as an EIC consultant and advised Captain Saris to set up the trading post in Uraga, conveniently close to his new fief as well as the ever-growing commercial centre, Edo. The EIC Captain, however, like the Dutch before him, declined and chose to base his operations in Hirado. Good for easy access to Asia, but weeks of travel from the main markets and cities of Japan where money was to be made.

This poor decision probably doomed the whole venture from the outset. It worked well enough while the English were permitted branch offices in the main city markets such as Osaka, but when Ieyasu’s son, Hidetada, later decided to impose greater controls on foreign trade, these were closed, and Japanese customers had to travel to Hirado themselves to access the English wares. Despite being moth-eaten, high-quality English woollen cloth generally sold well in Japan—provided it was the right colour. Only certain coloured fabrics, such as yellow, did not sell well. Given that, besides gunpowder, the goods were of poorer quality than those of other traders’ luxury Asian goods, and unsuited to Japanese tastes, it is understandable that business did not go as well as hoped.

By the end of this "rise to Samurai" period, Adams was already trading on his own account. In particular, he was trading on behalf of the Dutch and Spanish, as well as learning the ropes for independent trading.